Double Duty: Re-Imagining the Public Value of Infrastructure

Agency—Agency's Tei Carpenter unearths the latent placemaking potential of urban infrastructure, from fire hydrants to safety bollards.

The street as public space — as site to reclaim for civic possibilities — gained new potency during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement. Building on the roots of the Occupy movement, the Arab Spring and the social protests of 2015 (which brought attention to the re-appropriation of privately owned public spaces for gathering), streets increasingly operate as collective sites for both protest and everyday gatherings.

Streets are transforming into urban communication devices to assemble and broadcast support. With the demands of social distancing, they are also becoming pedestrian zones as roadways become sidewalks and as domestic spaces like living rooms spill onto sidewalks and stoops. Since the late 20th century, however, many major cities have increasingly turned towards securitization – and de facto privatization – of public space, harnessing design as a tool of protection and restriction.

PHOTO: Marylynn Antaki (Agency—Agency)

This tendency towards securitization also produces a visual language of defensive urban design. It manifests itself in a number of both visible and invisible ways that control and dictate how people can access the city. Consider the spikes installed on windowsills to deter entry, the armrests on benches designed to exclude the unhoused from sleeping, or myriad electronic modes of surveillance (such as CCTV cameras for traffic monitoring and GPS in cell phones) that can also be used to track people’s movement. Moreover, designing for safety in public space tends towards infrastructural engineering rather than infrastructural design, resulting in environments geared to the automobile rather than the body. But could one ask for whom — rather than for what — is the street designed? How might one recapture the street as a site for design to help nourish belonging, inclusivity, and spontaneous interaction in our public spaces?

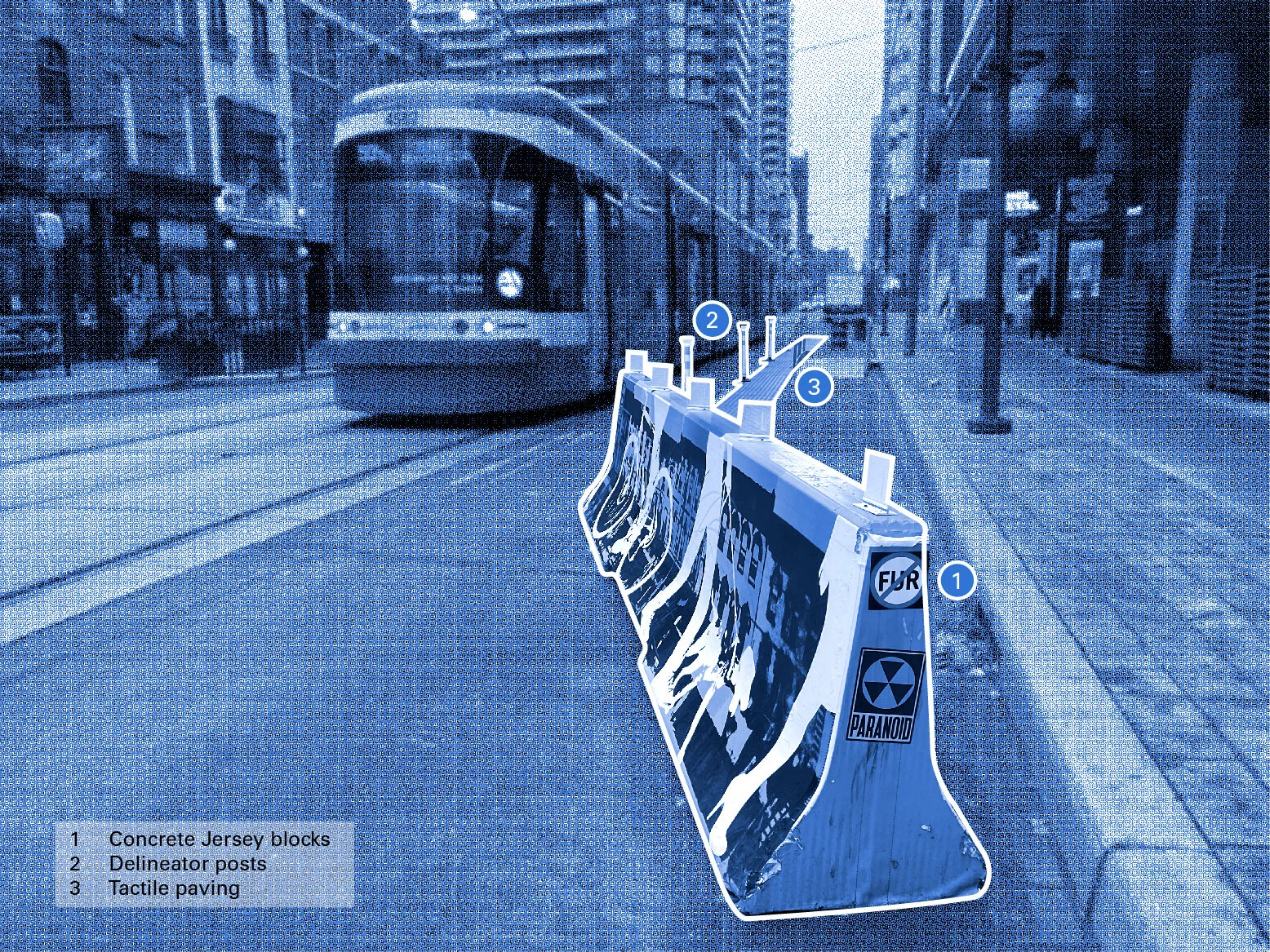

In my studio, we are engaged in working on the street as a public space to focus on the civic possibilities for designing and considering alternative uses for small scale urban infrastructures that are typically in the background of everyday urban experience. These elements, which include safety infrastructures such as fire hydrants, Jersey blocks, delineator posts, and traffic bollards, are often treated as an urban residue, leftover or forgotten artifacts that make up the city yet go unnoticed. The following offers three key frameworks that we would like to propose when thinking about safety infrastructures in public space.

Rendering by Agency—Agency (background photo by Ian Cheung).

Everyday Collective

Political expression does not just happen during times of emergency or calamity – it is embedded into everyday exchanges and unplanned interactions in the city. Infrastructural elements that act as civic resources and essential services of cities (for example that manage transportation, circulation, or the delivery of water) have a latent potential to support publics. They can become endowed with new aesthetic qualities and charismatic possibilities if attended to and designed with this in mind. While infrastructural elements may seem minor sites for design, they are connected to larger systems that proliferate across the city and can simultaneously operate at multiple scales.

As an example, our studio’s ongoing project New Public Hydrant transforms the emergency infrastructure of a fire hydrant into an accessible drinking water fountain or bottle fill station for everyday use, connecting the hydrant itself to the larger system of drinking water throughout New York City. Investment in essential safety infrastructures that are necessary for the functioning of cities, could be redirected towards designing social utilities that endow these infrastructures with the capacity to nourish an enriched collective civic experience.

New Public Hydrant. PHOTO: Agency—Agency

Double Duty

If infrastructure is typically designed with a singular functional purpose, we instead would like to think about the capacity for infrastructure to operate double duty. The Bentway perfectly illustrates this concept of an infrastructure that was created for automobiles as the Gardiner Expressway but which now works double duty as a public space of gathering and events on its underside.

The concept of affordances, coined by James Gibson, is useful here in that it describes the ways in which an object has the ability to invite certain actions due to its interactive features. For example, a door handle can be designed in such a way to either invite the user to push or twist the handle to operate it. Typically, however, safety infrastructures are distributed as acts of control throughout cities with little consideration for bodies or experience. But if the underlying characteristics of these objects are reconsidered, might there be alternative ways to engage them that could benefit the public?

As sociologist Harvey Molotch has described in his essay “Objects in the City,” it may be possible to consider inanimate objects in cities as actants which produce mutualistic relationships, generate particular choreographies of movement and “call forth particular behavioural repertoire(s) that becomes intrinsic to worlds of sociality and production.” Safety infrastructures such as crosswalks, traffic signals and traffic delineators, for example could be considered actants, as they choreograph the movement of people by identifying where and how to cross streets and direct ways of moving that become habitual in cities and produce relationships between people and the objects themselves. In this way, how can behaviours and habits of use affiliated with safety infrastructures be disrupted, nourished or re-conceived to reanimate public spaces in more interactive, inclusive and participatory ways?

New Rituals of Public Space

In my practice, we have been intervening on urban infrastructures in public space (many linked directly to safety) to investigate methods of endowing new rituals to everyday urban experiences. In our competition proposal Flatiron Crossings, for a site adjacent to the Flatiron Building in New York City, we reappropriated the language of safety infrastructures of traffic delineators and speed bumps to reassert them into an illuminated and immersive field, generating a universally accessible space to stop and interact within rather than merely move through.

Flatiron Crossings. PHOTO: Agency—Agency

In New Public Hydrant (a collaboration with artist Chris Woebken), a ubiquitous emergency infrastructure was similarly reimagined to deliver fresh water to the public in lieu of using plastic water bottles. Through a series of design probes, or “hydrant hacks” the designs transform the fire hydrant into an urban object that can oscillate between emergency use and everyday use, delivering water to the public in multiple ways: as an oversized bottle fill; as a multi-species fountain; and as a body-scaled microclimate.

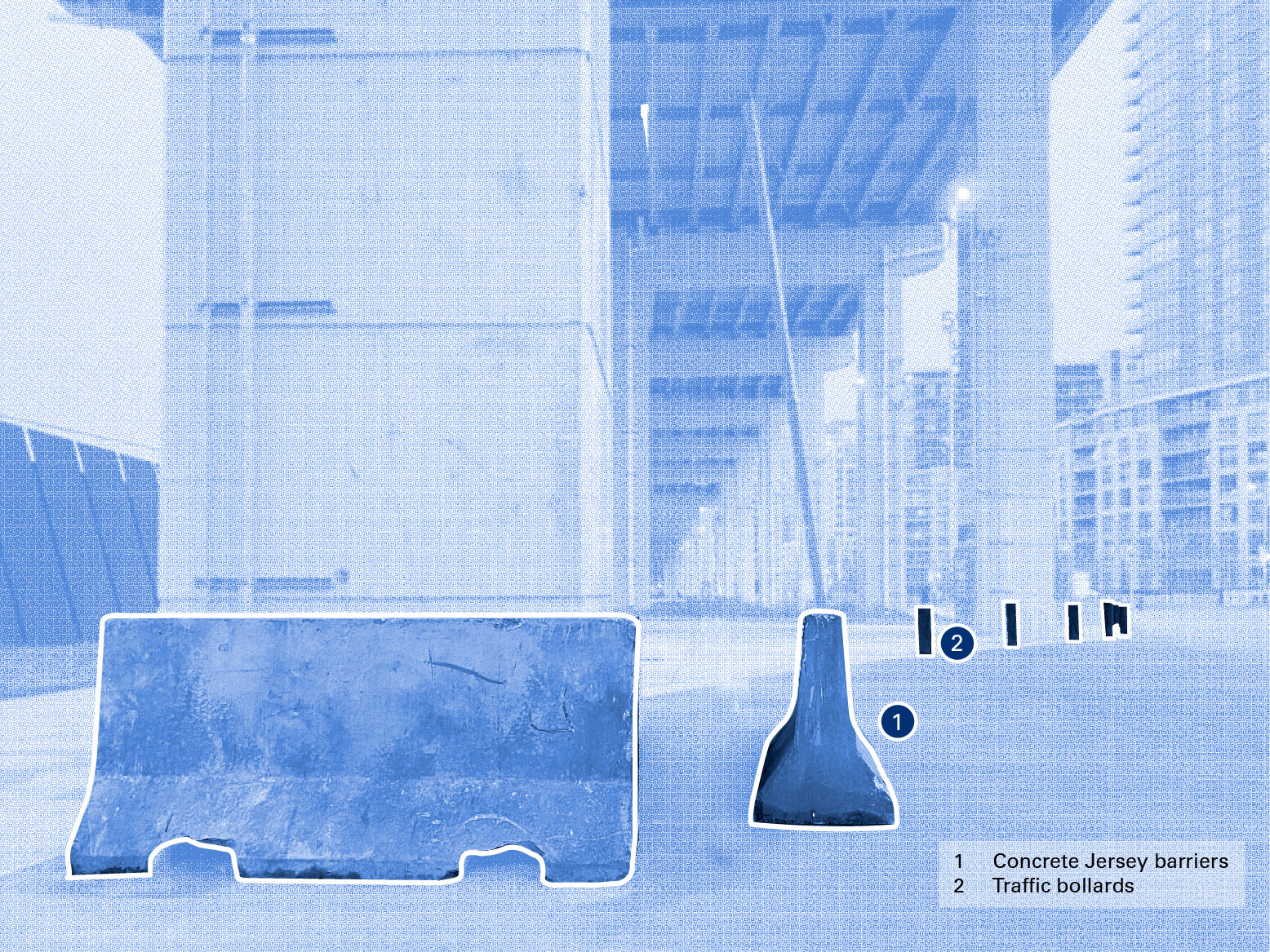

For the Bentway, we decided to investigate the affordances that the omnipresent modular concrete Jersey barrier might offer. Designed to be used as a traffic barricade to protect pedestrians and vehicles from collisions, it is often deployed along highways, construction sites or scattered across parking lots. On a recent walk along the Bentway, we captured two prototypical existing conditions, one directly underneath the Bentway (below, left) and one along the perimeter of it by an adjacent parking lot (right). On the Bentway site, the combination of the Jersey barriers and the traffic bollards beneath the Expressway produce an edge condition, a boundary delineating inside and outside.

Bentway current condition. Rendering by Agency—Agency.

Parking lot current condition. Rendering by Agency—Agency.

In our proposal, we rethink the sidedness of the Jersey barrier to re-specify an interior and exterior of the object through its profile. While any number of profiles might be possible, it could be as simple as introducing a two-sided profile system to the Jersey barrier to produce hospitable zones for seating and rest or homes for other welcome species that could take the form, for example of a planter profile. If new barriers and profiles were to be produced along these lines, a consideration for embodied energy must be taken into account to rethink the materiality of these infrastructures to support a more sustainable and resource-conscious approach to the production cycle.

Bentway reimagined. Rendering by Agency—Agency.

Parking Lot reimagined. Rendering by Agency—Agency.

In the parking lot illustrated above, the existing condition illustrates an unfinished, in-between area in the approach to the linear park, with guardrails and Jersey barriers marking a pathway protected from vehicles. Instead of viewing the Jersey barrier as a defensive object, our proposal rethinks the weight of the barriers as a ballast to support a flexible and easily repeatable and expandable play structures using arches and horizontal members embedded into the barriers. By marking the interior of the Jersey barriers as occupiable, this system could afford any number of activities including tire swings, hammocks, monkey bars, or lights for spontaneous interactions and gatherings. Meanwhile, the arches, delineated with colour, can also produce an identifiable threshold condition both moving inside of the barriers towards the Bentway or from afar when the barriers align. These two design proposals are just some of many approaches to consider new affordances that the Jersey barrier might offer within public space to support an everyday collective experience.

***

While the pandemic has brought the street into our consciousness in a new way, it is also a site of continued investigation into how infrastructures can produce social as much as functional utilities. In light of shifting urban conditions, the re-consideration of rituals and habits of use in public space is key to producing safer and more equitable public spaces.

This feature is one in a series of critical essays contributed by a passionate group of creators, artists, activists, researchers, and partners that will take a deep, critical look at safety and equity in public spaces. The Safe in Public Space essay series is co-published with Azure. For more on innovation, architecture and design, visit www.azuremagazine.com.